Hydrocephalus is a neurological condition caused by the excessive accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the brain’s ventricles. This buildup increases intracranial pressure and can severely impact brain function. Consequently, patients may experience headaches, nausea, cognitive impairment, or motor difficulties. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are essential to prevent long-term neurological damage. Among available options, hydrocephalus shunts serve as a vital intervention by safely redirecting excess fluid.

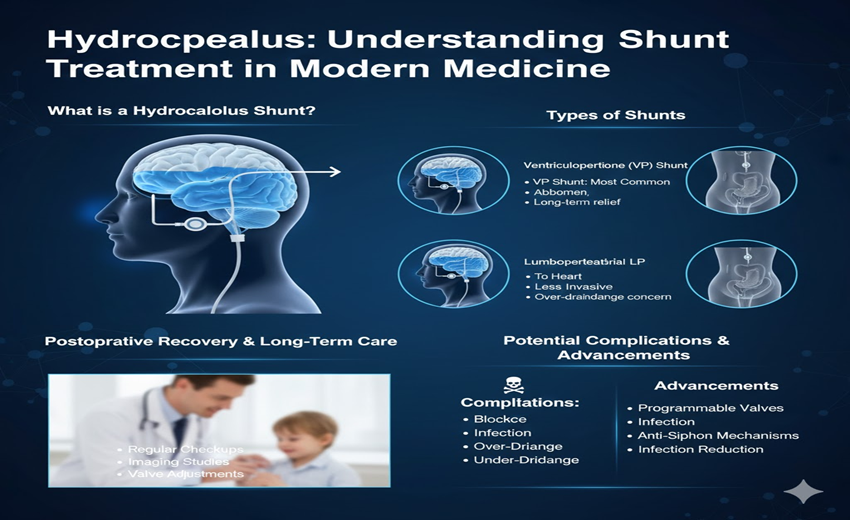

What is a Hydrocephalus Shunt?

A hydrocephalus shunt is a medical device designed to drain excess cerebrospinal fluid from the brain. It typically consists of two catheters connected by a one-way valve. One catheter removes fluid from the ventricles, while the other transports it to a different absorption site in the body. The valve regulates fluid flow, ensuring that drainage occurs only when pressure exceeds a safe threshold. Therefore, shunts effectively relieve intracranial pressure, reduce symptoms, and protect long-term brain health.

Types of Shunts

- Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) Shunt: The ventriculoperitoneal shunt is the most common type, diverting fluid to the abdominal cavity. It works well for both infants and adults, providing long-term relief. However, complications such as infection, blockage, or over-drainage may occur. Nevertheless, it remains the standard choice due to its durability and proven success in managing hydrocephalus.

- Ventriculoatrial (VA) Shunt: The ventriculoatrial shunt drains CSF into the right atrium of the heart. This option is suitable for patients who cannot tolerate abdominal placement. Nevertheless, it introduces heart-related risks, requiring careful monitoring. Physicians consider this type only after evaluating the patient’s overall health and suitability.

- Lumboperitoneal (LP) Shunt: The lumboperitoneal shunt drains fluid from the lower spine into the abdomen. It is less invasive compared to other shunt types. However, over-drainage is a concern, potentially causing complications such as collapsed ventricles or subdural hematomas. Therefore, careful pressure management is critical with LP shunts.

Preparing for Shunt Surgery

Shunt placement requires careful planning and preoperative assessment. Typically, surgery occurs under general anesthesia, and a neurosurgeon creates a small incision on the scalp. The catheter is tunneled under the skin to reach the chosen drainage site. In some cases, programmable valves are used, allowing doctors to adjust fluid flow after surgery. Patients and caregivers should discuss expectations, potential complications, and recovery procedures before undergoing the operation.

Postoperative Recovery and Long-Term Care

Recovery after shunt surgery involves monitoring for swelling, fatigue, or discomfort. Most patients resume daily activities within a few weeks. Long-term care includes regular medical checkups, imaging studies, and pressure adjustments for programmable valves. Shunts do not last indefinitely, and replacements may be required every 6 to 10 years. Maintaining consistent follow-up helps detect complications early and ensures continued shunt effectiveness.

Potential Complications of Shunt Systems

- Shunt Blockage: Blockages can occur when scar tissue or debris obstructs fluid flow. Such blockages increase intracranial pressure and may lead to a recurrence of hydrocephalus symptoms. Prompt medical attention is essential to prevent neurological damage.

- Infection: Infections may develop along the shunt tract or within the cerebrospinal fluid. Early signs include fever, redness, swelling, or headache. Immediate intervention with antibiotics or surgical revision is often necessary.

- Over-Drainage: Over-drainage occurs when too much fluid is removed, causing ventricles to collapse or subdural hematomas to form. Careful monitoring and valve adjustments reduce this risk and maintain patient safety.

- Under-Drainage: Conversely, under-drainage may allow fluid accumulation to persist, leading to headaches, cognitive issues, or neurological decline. Programmable valves provide flexibility to correct under-drainage without repeated surgery.

Special Considerations for Children

Children with hydrocephalus require particular attention because growth affects shunt function. As the child develops, the shunt may need adjustments to maintain optimal fluid drainage. Programmable shunts are especially advantageous, as doctors can modify pressure settings non-invasively to match the child’s needs. Additionally, parents should monitor symptoms and consult healthcare providers promptly if warning signs appear.

Support and Resources for Patients and Families

Living with hydrocephalus can be challenging, and emotional support is critical. Organizations such as the Hydrocephalus Association and Pediatric Hydrocephalus Foundation provide education, counseling, and community forums. Connecting with these resources allows families to share experiences, gain knowledge, and access specialized care options. Consequently, patients and caregivers feel empowered to manage hydrocephalus effectively.

Advancements in Shunt Technology

Medical technology continues to improve shunt safety and durability. Modern shunts include programmable valves, anti-siphon mechanisms, and materials that reduce infection risk. These innovations enhance patient outcomes and minimize complications. Researchers are also exploring alternative treatments, yet shunts remain the most reliable intervention for managing hydrocephalus today.

Conclusion: Shunts as a Lifeline

Hydrocephalus shunts do not cure the condition but are indispensable for managing fluid accumulation and reducing pressure in the brain. Proper care, timely monitoring, and patient education are critical for long-term success. With advances in technology and comprehensive support systems, patients with hydrocephalus can lead active, fulfilling lives. Ultimately, shunts provide hope and improve the quality of life for those affected by this neurological disorder.